How I Price My Work

Pricing can be a difficult thing. Here’s how I price my work.

A shortcut to your best art?

When I teach workshops I always have people work on several paintings at the same time. That way when you gets stuck you can merely move on to another one. The idea being that if you can keep moving – even if it is on a different painting that this is a good thing. The flow state of making art is the critical thing to keep one’s attention on, as it is this psychological space that allows strong art to occur.

When I teach workshops I always have people work on several paintings at the same time. That way when you gets stuck you can merely move on to another one. The idea being that if you can keep moving – even if it is on a different painting that this is a good thing. The flow state of making art is the critical thing to keep one’s attention on, as it is this psychological space that allows strong art to occur.

But then I discovered something else about how the creative brain works… and this was around making art when you are not really trying. It turns out, at least for me, is that when you are not trying so hard, often you can make your best art.

Who hasn’t struggled for days, possibly weeks on something only to work on something else that is just for fun and it instantly becomes better than that piece of art that you have toiled on for days, and even weeks?

What is going on?

If there are any shortcuts to making great art, then clearly this must one of them. If only we could do this all the time. It would make the process of art making much easier.

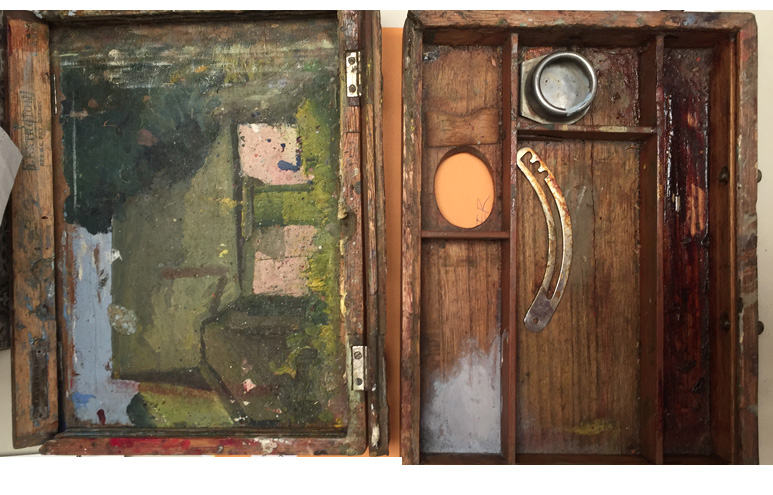

So now I always try to create this condition in my studio as well as my workshops. It has to do with what I call, the “throwaway board”. This is an additional 12″ x 12” board that is always sitting off to the side of the painting you are working on. When I am making small paintings in a workshop the throwaway board is also small but when I am in the studio and am painting larger then the throwaway board is large too.

The whole idea is that this throwaway board, (or canvas) is where you brush on your extra paint when you are changing your palette, or even just wiping extra paint off your brush. And yes it does end up looking pretty loose and raw but once you get in the habit of using this extra board, something interesting, over time, occurs.

The throwaway board becomes equally strong if not stronger than the actual board or canvas you are focused upon.

I don’t entirely understand what is happening, but now after about a year watching this repeat itself not only with me but also with dozens of students, I have come to a few conclusions.

1 When we try less hard sometimes our intuition can more easily express itself. In art, more often than not, our intuition is right.

2 If some of the marks we make are not totally controlled or thought through then the resulting art has more spaciousness. This more easily accommodates different viewers interpretations of this art making it generally more accessible to more kinds of people.

3 Because there is little or no pre-thought to what you are making on the throwaway board, only present moment spontaneous decisions to make a certain mark in a certain place, it makes the whole process super fast and incredibly effortless.

4 And of course last but not least, this painting off to the side of what you are painting really does make art that is strong. The last exhibitions I had, both had paintings that were derived from “throwaway” paintings. They were, in the end, the paintings I felt most apprehensive about at first but over time, realized they actually were among the strongest paintings I had made. Interestingly, both sold opening night and both were instrumental in giving me guidance as to where my work should be heading long after I made them.

Now, I can’t imagine art making without having a spare painting in my process with every painting I make. It has become that important to my process.

So maybe try this for yourself. Who knows, it could be that shortcut to your best art you never knew you could make.

I am curious about how this phenomenon shows up in your practice. Do you take advantage of it?

A Roll Of Paper Towels Is A Brush,

I always have a roll of paper towels with me… See why.

Get Yourself Unstuck

Sometimes you just get stuck. You are painting along fine and then you reach a point where you don’t know what to do. It might be because you have fallen in love and have lost objectivity. It might because the color is off somehow. But usually you stop and pullover because you just actually have no idea what to do. You truly have never been here before.

This is a good strategy in most circumstances. But in art, sometimes you think you can figure it out if you think hard enough, but in actual fact you can’t. It is hard to imagine too many steps ahead in a painting. Having no clear image to shoot for is somewhat terrifying but there it is. You have come to a place in the road that you can go no further. So logically we stop.

And then, since no new clear information is conjured up, we tend to stay stopped. Stuck.

So I don’t know the full answer, but I think I know a small part of it.

And here it is…

When you hit a roadblock, when you can’t keep moving in one direction, instead of stopping, you just go left or right. You pivot. In other words you keep moving in a way that is different even though you might not know the outcome. The important thing is to just keep moving. You might even be pretending to be moving towards something but if you can keep moving, if the dance can continue, the answer, the solution to what was stopping you arrives more quickly.

Interestingly, questions that arise in the process of making your art are often best answered from doing instead of thinking. If you can just keep mark making, faking it almost, then your art continues to change. It is this changing that actually starts to give you the crucial information about what you might do next. The changing art seems constantly new and fresh and as a result you can remain objective. And being objective allows you to see your art and what to do next, more easily.

So next time you find yourself just staring at your art not knowing what to do and minutes are turning into hours, just remember… Move. Take action even if you don’t know what to do. Do anything. Trust your intuition and simply dance.

That is a pretty good answer till a better once comes along.

And from my experience, it always does.

Do you ever get stuck? And when you do how do you get unstuck?

When your art will become amazing.

I recently did an interview with one of my favorite landscape painters Russell Chatham. There is always one question that I like to ask, especially when the artist is so seemingly far along in their art; when it appears that their art is so developed, so mature that it is hard to imagine it could get any better… when their art is simply an extension of who they are.

The question is this:

At what point in your career did you feel your work became more like you?

I know for me, for decades I felt I was struggling with trying to make something that I simply liked. Each painting seemed totally different from the first. And it happened almost every time I made a painting. Not only was I trying different materials but I was trying on different approaches, different ways of seeing and making art.

When I asked Russell this question he knew right away what I was talking about. He remembered.

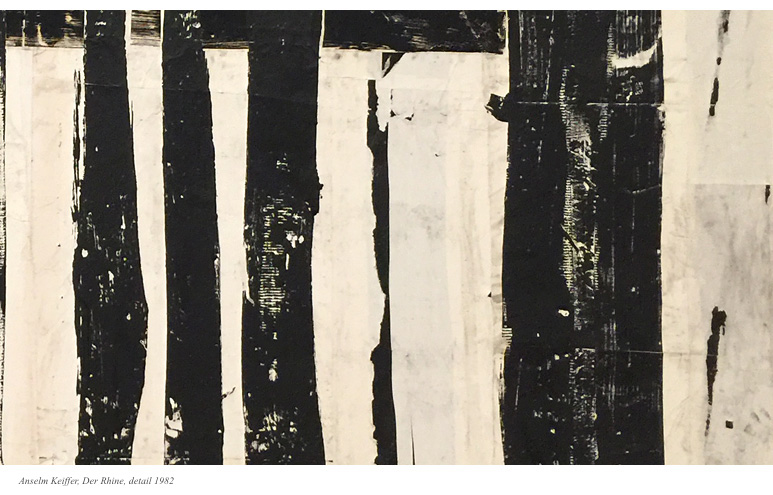

Being a self taught landscape painter, all of his early efforts were spent mostly standing in the wilderness, painting what he saw. He used a small painting kit his grandfather, the renowned painter Gottardo Piazzoni, had given him as a small boy. He described them as sketches. Small studies that described his surroundings.

It wasn’t until he needed to paint larger that his work began to take a more personal shift. One that began a process of editing, of winnowing-down to not so much of all he was seeing, but what he was feeling. All he remembered.

This began to occur because in order to paint large, he had to make the art in his studio. It simply was not practical to paint them outdoors in the elements. The pictures were inspired by nature, and places that he had been, but for the most part these larger paintings were made from memory.

And when this happened, editing occurred. It has to. Once the artist is filtering the information, instead of merely artfully recording what is seen, slowly a personal criteria emerges about what works and what doesn’t. The millions of yes and no decisions utilized in the making of your art begin to be made by looking within instead of outside of yourself.

This was certainly true for me. It took seemingly way too long to realize this concept. However maybe those criteria, that inner knowing of what resonates with you is not something you’re born with. Maybe it has to develop slowly, over time by spending countless hours looking outside of yourself.

In Russell’s case, decades were spent standing outside in all the places that spoke to him, that carried enough potency of place that he pulled his old truck to the side of the road, pulled his tiny painting kit out and began painting.

I am not sure if it is possible to get to that point where you are relying more on what is inside, rather than outside of yourself to make art, but I definitely see, not only for myself but with so many artists I meet, that once you do, that this is when the art really begins to develop. Authenticity, soulfulness and often, interestingly, desire for it by the outside world all increase. The more wild zig zagging of different looks or styles of approaching your art that come part and parcel with the early phase of a career settle down into a more cohesive direction. Everything begins to fall into place.

Again, I don’t think it is possible to game the arrival of this time in any way. You can’t bake a cake any faster just because you know the kind of cake you desire. But maybe there is some comfort, some small reassurance that for all of us struggling to find our way in our art that there is a place, probably not too far ahead for each of us, where we can make art that will feel and turn out more the way we want it to. Where the outcome will sometimes even amaze us or maybe it just might come a little more naturally. Like it is making itself.

I truly think that this begins to happen when the distance between who we are and what we make lessens – when that gulf, that distance between the two, becomes so small that the line is barely visible.

In other words, it is simply when your art becomes you.

Have you experienced this in your art making?

Welcome To The Studio

Come into my studio.

Jump.

In life there is a point where the risk of not doing something feels worse than the risk of actually doing it. ‘It’ being a move towards the unknown, the unrehearsed or anything at all that feels just out of our reach. Making art is actually the practice of making, again and again, these kinds of moves. They are scary but they punctuate our lives with poignancy and meaning. Much of our life slips from our memory but the times we followed our intuition, or took that step without knowing where we would land, rarely are forgotten. Especially the first time.

This week I offer a story, written by my daughter, Hannah, of one of those times. – NW

I was eight years old and my family went on a bike trip through Austria. Starting at the German border and winding our way through the beautiful countryside to Vienna, we stopped for lunch in small cobblestone towns and rustic inns. Everything was a bit strange and new to me. I recall hesitantly tasting from a traditional breakfast buffet of mysterious cold cuts and cheese, learning to change gears on my bike, and listening to the strange sounds of German and Austrian families squabbling over lunch.

Caution and fear were constant companions to my eight-year-old self. In fact, I remember being scared of a lot of things—bears, airplanes, fires, being lost or separated from my family, losing a tooth. Every night before going to sleep in a new place or at a friend’s house, I would thoughtfully run over my escape plan just in case the house flooded or was engulfed into flames. Living alongside two fearless parents who had traversed the whole globe, sailing through a tropical storm around the Fiji islands, perhaps I felt someone in the family needed to be practical.

After one particularly long and hot, dusty day of riding, we stopped at a water park in Melk, just outside of Vienna. My mom and dad rested under the shade of a tree as my sister, Lyla, and I went to explore the complex tangle of slides, tubes and diving boards. It was my first time at a water park. You can imagine my horror as I watched thousands of kids twisting through tubes and shooting out from different portals and slides into a giant pool of overly chlorinated water. Shrieks and screams reverberated off the inside walls of this giant plastic dome, and sent me wandering outside.

I don’t think I will ever be able explain my next move. Or what propelled me to climb the 35-foot diving board latter. But somehow I found my toes hanging off the edge of that diving board looking down into a deep pool of shimmering turquoise below. Goggled and knees turned in, I looked behind me at the line of impatient teens waiting to jump…there was no turning back. And for some reason the voice inside my head that often told me to turn back said, “Hannah, this is your time. This is the day you will stop being scared.”

Perhaps it was the kind of choice I faced—heroically jumping into the diving pool or sitting with my mom watching other kids splash and play—that no longer felt like a choice. Holding onto a lot of “no’s” and missed experiences, I felt that the only way out, the only escape route was to jump and choose “yes”.

So I jumped.

My stomach turned over and flipped in my body as I awkwardly fell down to the water like a bird paralyzed, shot out of the sky. Upon hitting the water, I knew that jump had changed everything. So when I walked over to my parents and told them what happened, it didn’t really matter to me that nobody believed my story. It was a powerful and silent shift…and I liked that I was the only real witness to my extraordinary dive.

I still don’t really like heights. I’m not the kind of person that gets nauseous riding a tall elevator to the top of a New York skyscraper, but I also don’t intentionally seek out heights or adrenaline-producing, extreme sports. However, every time I encounter the chance to jump, I do it. Whether leaping from a tall diving board or off a rock into the sea in Greece, when I hit the cold water, something is once again reaffirmed in myself. Something about the sensation of jumping relights that glowing, fiery feeling of uncertainty and excitement inside of me. It reminds me that I am alive and have the agency to do whatever or be whomever I want.

I’m not advising anyone to exist in constant chaos or live on the edge, fling yourself from the tall bridges, or rock climb the face of Half Dome. But I do think it’s incredibly valuable to find your own small way to step outside yourself, even if that sometimes means that you have to fake it. The girl that jumps off tall rocks into the dark blue ocean isn’t necessarily me; but she gives me a taste of what it means to be wild and utterly free, reminding me how good it feels to just jump.

How can you wholeheartedly and completely let go? What is your “jump”? Because that feeling, that zing, is what we are all chasing after. Its what reminds us that we are alive. Try to step outside yourself, even if for a moment, and open to the possibilities that might exist just beyond.

What is your Jump?

In gratitude,

Nicholas and Hannah

What About The Sides?

It’s important not to forget about the sides of your painting… Here’s what I do with mine.

That Thing, Again

There is this thing that I know. It has to do with making your art – no matter what discipline you create in – more authentic. I am now convinced, from my personal experience that it is one of the primary pieces of information needed to make remarkable paintings. This little bit of knowledge, this small smackeral of understanding not only helps your art go from good to great, it also relates – at least for me – to almost every aspect of my life. The problem is, that for some reason, I keep forgetting about it. I am not sure why, but I do. Constantly.

When I remember it, I feel a lightness wash over me. It feels a little like getting away with having your cake and eating it too – only in this case there are as many servings as you can imagine.

Does this idea always work? When didn’t it? So has it been this easy all along and it was just me making it so damn hard? When you remember it, things just turn out easier, better, especially art. Problem is, even though I teach this to people, I forget it sometimes. I forgot from Friday morning until today, Wednesday afternoon at about half past three, to remember it again. Once I did my paintings started improving in a way that till today I had been unable to imagine. I sensed I wanted things to be different, but I just didn’t know exactly how.

Sometimes I think I am just unable to hold things in my brain. As a teacher, a big part of my job is simply to remind people again and again of what they already know. Repeatedly they say the same thing to me…”I can’t believe I forgot that AGAIN!” I reassure them that when you are standing in front of a panting it is so absolutely transporting that often that you can leave a part of your thinking behind – everyone does this.

So what is this idea? So before I forget again, here it is….

Try to make your Art MORE from what you FEEL rather than what you THINK.

If you do, your work gets more personal. It is simply more like you. And lo and behold if it is, if it is a reflection of what you FEEL, then it will be more AUTHENTIC. And when that happens it changes from garden variety good, to amazing.

Give it a try.

In forgetfulness, Nicholas

Let A Madman Work On Your Art Pt. 2

In one of my previous blogs I spoke about using an orbital sander (check it out at https://www.nicholaswilton.com/2016/07/31/let-a-madman-work-on-your-art/).

Here is how I use it…

https://www.ryobitools.com/products/details/187